What are the biggest threats colleges and universities face today? You might mention rising tuition rates or the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on classroom teaching – but there’s something else creeping onto campuses at an alarming rate.

Much too often, we’re hearing stories like these:

- The Los Angeles Police Department stepped in during the fall of 2019 to help administrators at USC determine whether opiate overdose might be a common link in the deaths of nine students at the university.

- Early last year, the parents of Madeline Globe announced they were going public with the story of their daughter, a senior at the University of Colorado Boulder, who died after taking an opiate-laced pill she thought was a prescription mood stabilizer.

Two seniors at the University of Nevada Reno died just a few months before they were expected to graduate. Both had taken pills they thought were safe, but turned out to contain traces of a powerful and dangerous drug: fentanyl.

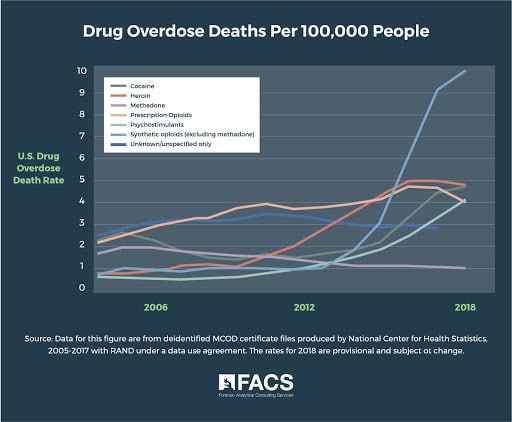

Laws aimed at tightening the availability of prescription opioids are lowering the number of deaths from prescription painkiller overdoses, but colleges across the country are reporting student overdoses attributed to street drugs. No state or region is exempt from the threat.

The opioid epidemic is gaining in public awareness, but one aspect of the problem gets little attention: Drug residue can expose others to severe health risks – whether they are users or not. That means anyone who accidentally inhales or absorbs drug residue is threatened. Children are especially susceptible.

It is crucial for college administrators and those who manage residential housing to become aware of the issue. Ingesting just two milligrams of fentanyl can kill an adult. Think of what could happen from inadvertent exposure to a tiny amount of the drug in a college housing unit.

Once you’ve become aware that non-prescribed opioids have been found on your campus, you are obligated to search for and identify any residue, remove it safely, and confirm the effectiveness of the cleanup procedure. Never allow untrained personnel to attempt the job. The potential ramifications of an insufficient or improperly conducted procedure can be devastating.

The photo above shows two milligrams of fentanyl – a lethal dose for most adults (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration).

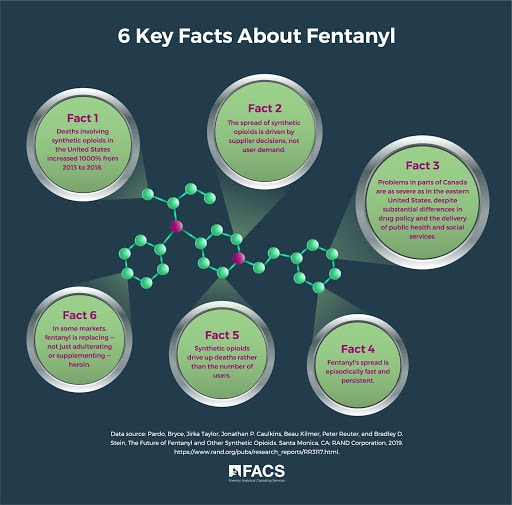

Why Fentanyl Use is Booming

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is relatively inexpensive and is readily available online. Drug dealers combine fentanyl with other drugs to increase their profits. Fentanyl allows them to deliver the same volume of product at the same price as usual, but with less cost to themselves. Consequently, the user is usually unaware of the hidden danger.

A recent RAND Corporation report declared Fentanyl the most dangerous illegal drug in America. It contributes more to the burgeoning opioid epidemic that takes more lives than “car crashes, gunshots, or AIDS at its peak.” Many of the at least 30,000 people who died from synthetic opioid overdose in 2018 had no idea they were subjecting themselves to the real risk of sudden death.

The Hidden Danger

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) database lists fentanyl as an incapacitating agent estimated to be “hundreds of times more potent than heroin.” The drug can be inhaled, taken orally, or absorbed through the skin. It can even be administered as a liquid spray.

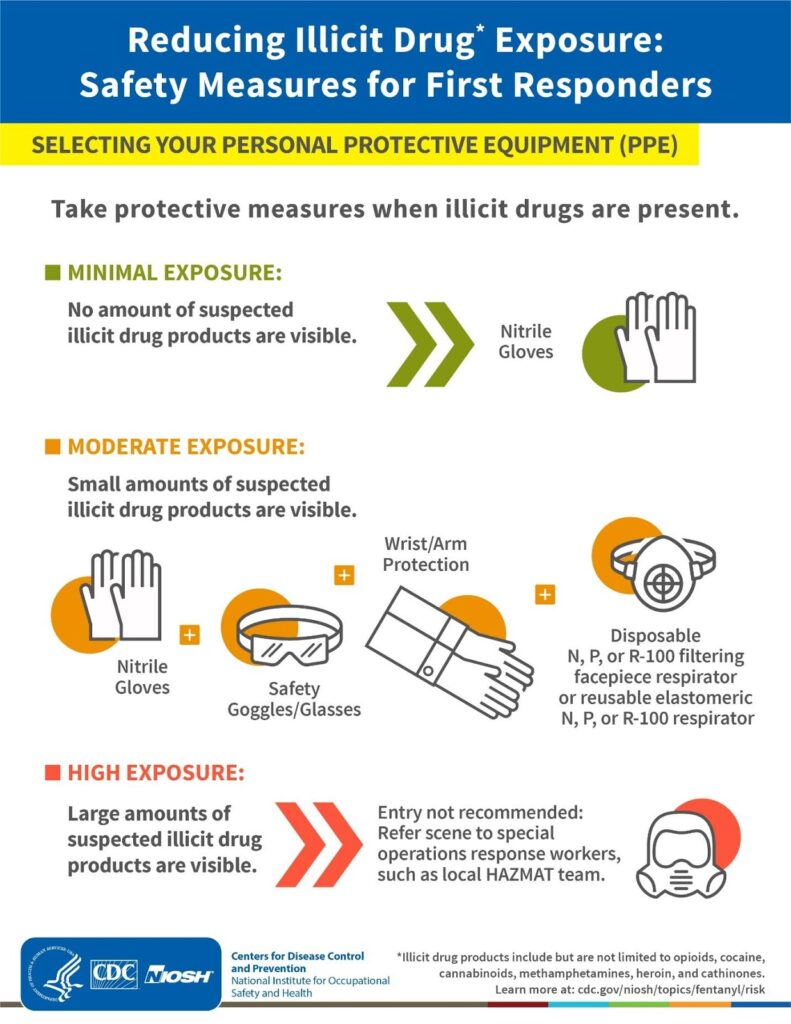

NIOSH developed the following list of key recommendations for emergency responders who encounter a scene where illicit drugs are suspected:

- Always wear nitrile gloves when illicit drugs may be present, and change them properly when they become contaminated.

- Wear respiratory protection if powdered illicit drugs are visible or suspected.

- Avoid performing tasks or operations that may cause illicit drugs to become airborne.

- Do not touch the eyes, nose, or mouth after touching any surface that may be contaminated, even if wearing gloves.

- Wash hands with soap and water after working in an area that may be contaminated, even if gloves were worn. Do not use hand sanitizer or bleach.

- Take training on and follow NIOSH’s recommended Standard Safe Operation Procedures.

An Oklahoma police officer collapsed last year following exposure to fentanyl-laced methamphetamine following a traffic stop involving illegal drugs. A police officer in Maine was hospitalized in May following inhalation of fentanyl during a routine investigation. And an overdose at a California hotel led to a hazmat response by the Los Angeles Fire Department to decontaminate the affected room and ensure additional sections of the property were not a hazard to guests.

When a college housing unit is the scene of an opioid overdose, the situation escalates beyond the immediate medical issue. It is essential that the area be cleared of drug residue to protect others who may enter the premises.

A CDC/NIOSH infographic for first responders. Note that overdose cases are considered moderate exposure unless large amounts of an illicit drug are seen.

How to Clear Exposed Areas of Fentanyl and Other Drug Hazards

Please note: This isn’t a job for maintenance staff, unless proper equipment and training is arranged beforehand. If police officers can fall victim to fentanyl exposure, it’s certain that untrained workers entering a suspicious area are at an elevated risk.

There are several components involved in clearing a contaminated area:

- Ensure that a proper scope of work is developed prior to beginning. The initial assessment should identify the locations and level of impact to the space.

- Allow only those who are trained in the cleanup of hazardous materials to enter the area. Control traffic quickly to prevent inadvertent exposure.

- Require everyone entering the space to wear approved personal protective equipment (PPE) that is adequate to the level of the threat.

- Include both a visual inspection and surface sampling of representative surfaces in the initial assessment.

- Segregate and wash (or properly discard) all contaminated PPE, supplies, and clothing.

NIOSH offers an in-depth look at safe practices (including a video of what happens when a first responder is exposed to fentanyl) on their website. Here is that link: Illicit Drugs Tool-Kit page.

Neither this article nor the NIOSH toolkit should be considered sufficient instruction. Our purpose here is to help get the word out. You can join FACS in that effort by forwarding this article to the school administrators and property maintenance workers in your region.

For more information, or to request advice related to a specific incident on your campus, call (888) 711-9998. You can also use the FACS Contact Form.